Sister Pat Hogan reflects on her and Sister Susan Dunn's visit with the Shinnecock Kelp Farmers. Photos were taken by Sister Susan Dunn.

Shinnecock, Noyack, and Peconic were part of the “geography” of my childhood. Crystal clear bays provided hours of “being one with the water” while actively swimming, crabbing, clamming, and fishing. Fish dinners and Mom’s famous Manhattan Clam Chowder provided many of our summer suppers.

My whole family treasured our summers in a cottage on Little Peconic Bay. Pristine waters provided entertainment as we watched schools of minnows, shiners, and blowfish. It was exciting to view a horseshoe crab crawling on the bottom of the shallow waters. My dad once explained that horseshoe crabs dated back to Prehistoric times and continued to flourish in these healthy bays.

Walking along the shoreline, we would collect many beautiful shells, my favorite being the scallops. Harvesting delicious, sweet, “bay scallops” took place in the early fall along with catching fresh blue fish! Oyster, mussel, and clam shells left behind were due to the ravenous seagulls and pipers who feasted on them daily while the Osprey dined on varieties of large fish.

We treasured every summer we had growing up in the 1950s and 1960s. As we neared Labor Day, my Father would take me to a portion of the Shinnecock Reservation to visit the women and men who had a shop in the shape of a Teepee. I was treated to a little doll or beaded bracelet that the women made. He would chat with the proprietors and later, on our return to the cottage, Dad would share the history of the indigenous people on the East End and how the land they lived on for centuries had been parceled off by the government and sold to developers. I remember that made me feel sad.

Pope Francis has urged governments and the international community to respect the cultures, dignity, and rights of indigenous peoples, acknowledging their crucial role in helping address the current global environmental crisis.

This past year's Indigenous People’s Forum, focused on Indigenous Peoples’ Climate Leadership: Community-based Solutions to Enhance Resilience and Biodiversity. Pope Francis remarked that the theme of the forum offered an opportunity to recognize the critical role indigenous peoples play in protecting the environment and an opportunity to “highlight their wisdom to find global solutions to the immense challenges that climate change poses to humanity on a daily basis.”

Fast forward to today, my nephew, nieces, and their children are searching for fiddler crabs, collecting mussels, looking for turtles, swimming, and kayaking in Little Peconic Bay. But because of “climate change” they have decided not to eat the shellfish. People who farm oysters are struggling due to warmer waters; fishermen are having difficulty, as well, because of the influx of bacteria. The Brown Tide stunts oyster growth, requiring more time to bring oysters to market size--a major obstacle for oyster farmers. Brown Tide usually appears after the spring algae bloom has depleted estuaries of inorganic nutrients.

This past summer, many of our Sisters made a retreat at the Brentwood Sisters of St. Joseph Villa, New York, located on the sparkling waters of Shinnecock Bay. It was there that we learned about the indigenous women of the Shinnecock tribe and their efforts to farm “sweet kelp” in order to help bring back healthy vegetation that will assist in purifying the bay, thus giving the shellfish and other forms of sea life a chance to grow stronger.

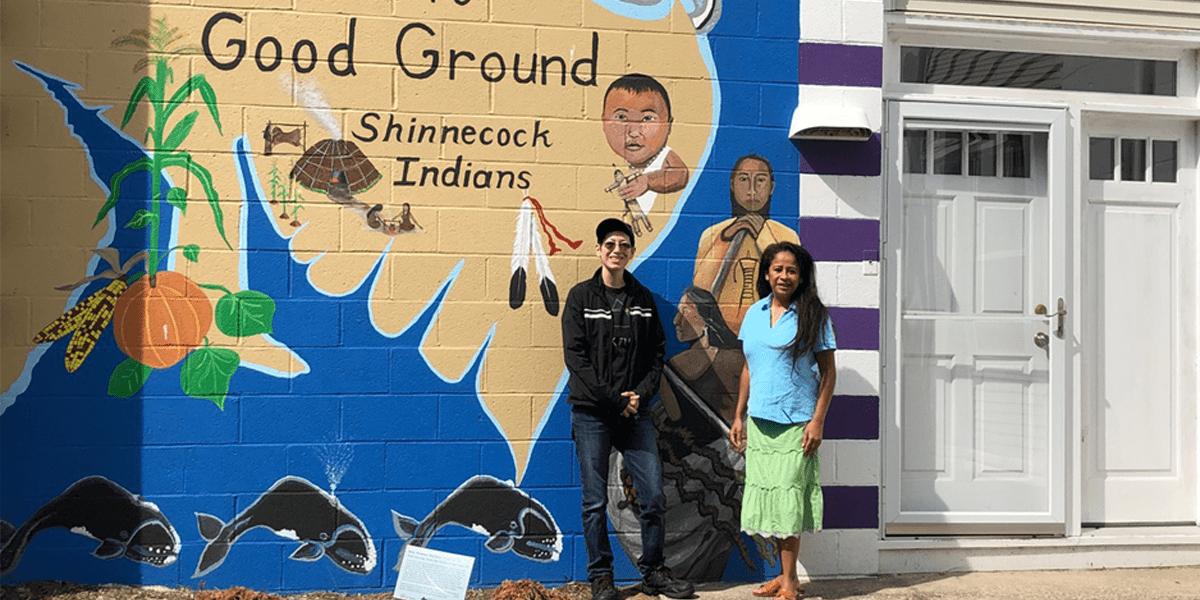

Danielle and Waban, the Shinnecock women behind this project welcomed us on the Sisters of St. Joseph’s property and began our visit with an explanation of the “mural” on the wall of the Retreat Center. It told us much about the life of the Shinnecock tribe. There was a time when the “reservation” was much larger, and the sacred ways of fishing and farming were done in the tradition of these people who took and gave back to Earth. The sweet kelp was cultivated during the cold season and, when it was long enough, dried for food, spices, and fertilizer to grow crops.

Painted on the mural is a woman in a canoe harvesting the kelp as well as corn and pumpkins that grew abundantly because of the sweet kelp fertilizer. Now, several indigenous families are striving to bring back the “ancient ways” of living by caring for the waters, as well as the land, and respecting all life. This has become a collaborative effort of the Shinnecock people who are joined by the Sisters of St. Joseph of Brentwood, Stony Brook University, and a robotics class from Mary Louis Academy High School in Queens.

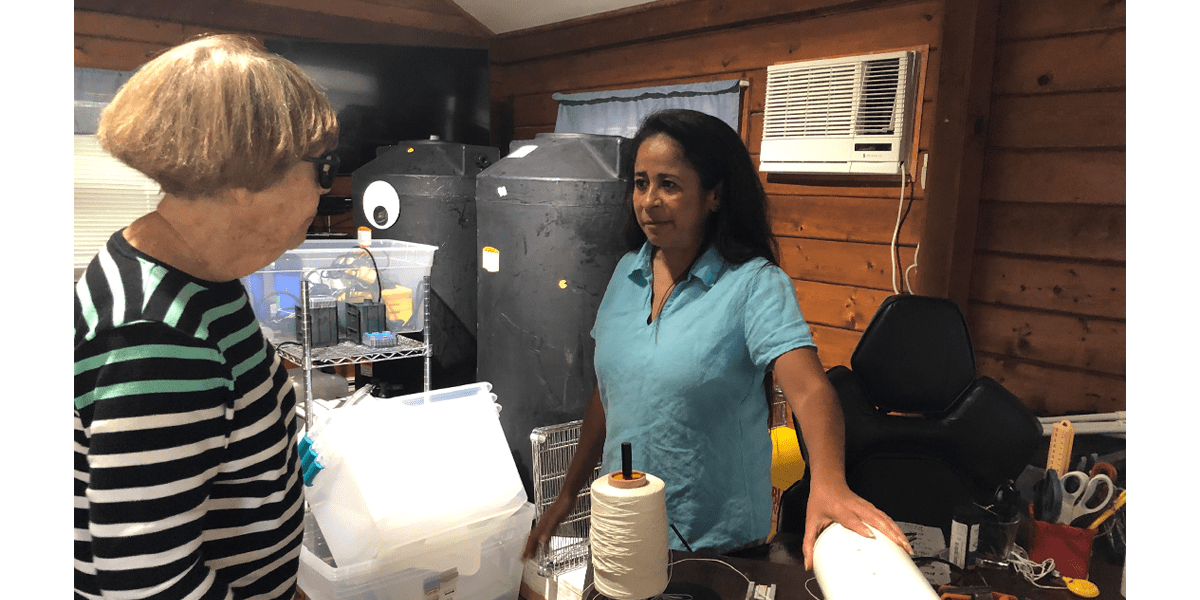

The Sisters provided a lab, Stony Brook University, two large tank coolers, and gallons of pure sea water, and the students at Mary Louis Academy invented a machine to thread thin lines into incubators filled with cold water. Spores of sweet kelp are then placed on the lines in the incubator and monitored until they are an appropriate size. The kelp is then placed onto thick rope in the bay where they will grow to a certain length. While this process is happening, the kelp releases good oxygen that supports other vegetation as well as the shellfish growing in the sand.

We should listen more to indigenous peoples and learn from their way of life to properly understand that we cannot continue to greedily devour natural resources, because ‘the Earth was entrusted to us in order that it be a mother for us, capable of giving to each one what is necessary to live’. Therefore, the contribution of indigenous peoples is essential in the fight against climate change. (Pope Francis)

Pope Francis has called upon governments to recognize the indigenous peoples “with their cultures, languages, traditions, and spiritualities,” and to respect their dignity and rights. He said, “Ignoring the original communities in the safeguarding of the Earth is a serious mistake, not to say a great injustice.”

When people don’t respect the good of the environment, our common good, they become inhuman, because they lose contact with Mother Earth, not in a superstitious sense, but in the sense that culture gives us harmony. (Pope Francis)

Indigenous peoples know this too well. Therefore, the Pope insisted, “Aboriginal cultures must not be converted to a modern culture,” but “need to be respected” and allowed to follow their own path to development.

We should listen to their wisdom.

We are grateful to Danielle, Waban, and the indigenous women of the Shinnecock tribe who explained to us the need to “heal” the waters in the bays. For Sister Kerri and the Sisters of St. Joseph who have a Spirituality Center on Shinnecock Bay and who provide a building that is transformed each fall into a lab of life. By tending to the water and the land, they have witnessed their loving respect for and faithfulness to the Creator.

Visit these links for more info:

PBS Video, 'Peril and Promise'

Shinnecock Kelp Farmers and Sisters of St. Joseph Collaborate to Cleanup Bay

– Sister Patricia Hogan, OP

Sister Pat is a Pastoral Associate at St. Francis of Assisi Parish in West Nyack.